|

That was the defining moment, but it wasn't really where it all started. We weren't even The X-Hunters then. In fact, we barely knew each other.

Our separate but converging paths began in elementary school. We both grew up with an interest in airplanes and spacecraft and the people who tested them. We loved exotic airplanes like the X-15, XB-70, and SR-71. Our heroes were men like Fitz Fulton, Iven Kincheloe, and Mike Adams who flew these planes at Edwards Air Force Base in the Mojave Desert.

In the mid-1970s I bought a book about the Northrop flying wings, tailless airplanes that had no conventional fuselage. I read that one of these, the YB-49, was lost in a fatal accident in June 1948. Edwards AFB was named after the pilot, Capt. Glenn Edwards. The author of the book noted that visitors to the YB-49 crash site could still find pieces of the airplane scattered in the sand. This thought intrigued me, but I wasn't able to pursue it for another decade.

Tony was similarly intrigued by the XB-70. The second of two prototypes crashed near Barstow, California, in June 1966. While in elementary school, Tony saw a photo of the wrecked bomber in a book. He wondered even then if it might be possible to find pieces of it.

In May 1982, I joined a group of people for a hike to the top of Mt. San Gorgonio, an 11,500-foot peak in San Bernardino County. I was surprised to discover that the trail passed through the wreckage of a C-47B cargo plane that crashed in 1952. It appeared that the entire shattered airplane remained on the mountain. This was the first crash site that I had seen in person.

In May 1984, my friend Mark Miller saw metal pieces gleaming in the sunlight near the top of Mt. Williamson in the San Gabriel Mountains. He figured out the best route to hike up there and we set out to find what appeared to be an airplane wreck. It turned out to be a C-119G that crashed in 1966. The wreckage was scattered on both sides of a ridge above the Devil's Punchbowl. Again, it appeared that the entire airplane had been abandoned-in-place. It was interesting to see the wreck and it was fun trying to figure out how to get to the site. Hiking up the mountain was a nice adventure for a fine spring day. It didn't generate enough interest, however, to make me want to turn wreckchasing into a hobby.

In 1985 I met Dr. Richard P. Hallion, then Edwards AFB chief historian. In his office he showed me two large pieces of aluminum wreckage that someone had found in the desert east of Mojave. The person who found them claimed that they were from the Northrop YB-49. Nearly two decades later, I identified those same pieces as parts of a McDonnell KDD-1 target drone, but in 1985 they inspired me to look for the YB-49 crash site. Dr. Hallion gave me some helpful hints for finding it, but it still took me nearly four hours to locate the spot from which Edwards AFB got its name. Just as the book had described, the ground was littered with small pieces of metal and plastic from the flying wing. It was here that I first learned the importance of part numbers and inspection stamps to positively identify aircraft debris.

Soon I began to think about the XB-70. On 8 June 1986, I made a fairly lackluster attempt to find the crash site near Barstow using the limited information available to me. I failed to find it, but I vowed to get more information and try again.

Tony was also thinking about the XB-70. In 1989 he stopped in Lancaster to check out an aviation collectibles store called Thomas Aviation. There he saw a photo of the store's owner Tom Rosquin standing in the desert holding pieces of the XB-70. Tony questioned the sales clerk, an elderly lady named "Smitty" about the crash site location. Smitty told him to "look near the radar dish." Tony thought that meant the Deep Space Tracking Station at Goldstone and ended up making a fruitless search in the vicinity of Superior Valley.

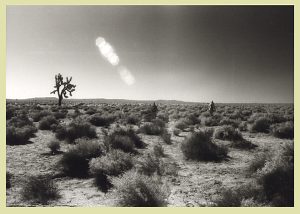

After spending a great deal of time and effort, making several journeys to the Barstow area, and questioning Tom and various Barstow locals Tony wasn't about to give up. Tom ultimately provided enough clues to get him into the right area. Tony had been studying old photos of the crash site until the images were burned into his brain. As soon as he got close to the site, he experienced an intense sense of deja vu. He recognized a distinctive large Joshua tree and knew he had arrived. Stepping out of the car, Tony spotted a metal fragment with white paint on one side and stainless steel honeycomb on the other. He had found it!

I also visited Thomas Aviation in 1989 and saw the same photo. Tom was never in the store when I visited Lancaster so I never had a chance to ask him about the site location. At the time, I was working for Skywest Airlines at Burbank Airport. Our airplanes were fueled by a company called ASI, Inc., but a few years later we switched the fueling contact to a company called Mercury. Each day, the Mercury truck pulled up to our gate and I greeted the fueler and told him how much avgas we needed. We rarely talked about anything else. I noted that his name badge read: TONY MOORE.

On 4 May 1992, I returned to work from a two-week vacation. Tony remarked on my absence and I regaled him with tales of my trip. I told him that I had been exploring ghost towns, mines, caves, nuclear test sites, and prehistoric rock art in California and Nevada. Tony remarked that he liked to look for airplane wrecks. "You would have liked this trip," I said, "we visited the crash site of a Convair 340 near Bishop." Then Tony uttered some fateful words: "I've been to the XB-70."

The next day, I brought a topographic map of the Barstow area to work. I showed it to Tony and asked where the XB-70 crash site was located. He had worked hard to find it and wasn't quite willing to tell me exactly where it was. "It's right around here," he said, indicating about a two-square-mile area. That sounds pretty manageable until you are standing in the middle of it. It's a big desert.

I had a secret weapon, however. On one of my visits to the Edwards AFB History Office I had acquired a photo that showed smoke rising from the burning wreck of the XB-70. There were a number of dirt roads and gullies in the surrounding terrain that seemed distinctive. I compared the photo to the area that Tony had indicated on my map and marked the spot that seemed the same on both. The following Sunday I drove to Barstow to test my theory. As soon as I saw the Joshua tree I knew I had found it.

On Monday I told Tony. He was impressed that I had located the site so quickly. We discussed other airplanes that had crashed and found that we had a mutual interest in experimental planes and the history of Edwards. "So, what should we look for next?" I asked. Tony answered without hesitation: "The X-15."

We began our research in earnest. On Friday, 26 June, we drove to Edwards at the crack of dawn to visit the History Office. We had to be back in Burbank by noon for work. We repeated this performance on Wednesday, 8 July. Tony joked that we should call ourselves "The High-Speed Research Team."

|

Inspired by our success, we decided to find the X-2 crash site. We soon discovered that we each had special talents and abilities that made us a highly successful team. Over the next several months we found the X-2, NF-104A, and an SR-71; and that was only the beginning.

Mostly we continued to specialize in experimental aircraft dating from about 1940 to 1970, the "Golden Age of Flight Test." We felt it was more challenging than looking for warbirds (WWII-vintage aircraft) because the sites had been more thoroughly cleaned up than those of most conventional aircraft. Whenever we told someone what we were looking for, the usual response was that "there's nothing left, it was probably all cleaned up." We soon learned that there is always something left if the site hasn't been paved over. We always make sure to positively identify the artifacts we find. If we find aircraft parts in the correct geographic location, that's a pretty good indicator, but we like to take it a few steps further. Debris can be identified by part numbers, materials, construction methods, and even types of paint. Usually we get lucky and find unique, positively identifiable components.

At first, we were just doing it for the thrill of finding pieces of our favorite airplanes. We were touching a piece of history and it was a real adventure! The research portion of each hunt was a chance to play detective and the field portion was a journey into the outback of the Mojave Desert. We were like Sherlock Holmes and Indiana Jones rolled into one.

Locating a site is not always easy. Research is the key. We spend many hours in libraries and archives before venturing out into the field. Sometimes we have the opportunity to interview eyewitnesses for a first-hand account. Even this is not always enough. It's a big desert out there if you do not have the exact coordinates and there are numerous natural hazards. In spite of the difficulties, or perhaps because of them, it is always an adventure finding these oft forgotten places.

Some people will tell you that none of these famous sites were ever lost. The sites were, in fact, carefully investigated, photographed, and documented. After the cleanup, however, they were abandoned and mostly forgotten. The locations were often not accurately recorded in newspaper articles and even accident reports. Pilots who survived the accidents usually didn't care to know where their airplane ended up. People who worked on the recovery crews never returned and rarely made any effort to remember the details of the crash locations. Even local residents are often unaware of the history beneath their feet or (sometimes literally) in their back yards.

|

In 1994 a freelance writer named Lance Thompson heard about our exploits through mutual friends and thought it would make a good story. After meeting Lance, we invited him to join us on our search for the X-1A crash site. He wrote a wonderful article and offered it to Aircraft Illustrated, Air Classics, and AIR&SPACE/Smithsonian magazines.

Perry Turner at AIR&SPACE accepted it for publication in the March 1995 issue. Since we primarily researched experimental aircraft ("X-planes"), Perry thought that should be reflected in the title of the story. And so, he called us "The X-Hunters."

Peter W. Merlin

The X-HUNTERS

Aerospace Archeology Team

Edwards, CA

December 2004